| +Home | Museum | Wanted | Specs | Previous | Next |

Monroe 920 Desktop Calculator

Updated 2/26/2023

The Monroe 920 an example of US-based calculator company Monroe leveraging Japanese calculator design and manufacturing capabilities to deliver a low-cost, entry-level electronic calculator to the marketplace, during a time when it would have been nearly impossible to produce a calculator of their own that would have been price-competitive. Monroe forged an agreement with Canon sometime in the 1968 to 1969 timeframe whereby Monroe could re-sell Canon-designed electronic calculators under the Monroe brand, with differences in cabinetry, and sometimes minor (designed-in) differences in function, to distinguish the Monroe calculators from Canon's. Monroe marketed, distributed, supported and serviced the calculators as their own. The Monroe 920 is nearly identical to the Canon 120 and Canon 1200 models, with the differences being subtle keyboard layout changes, and color schemes for brand differentiation. The Monroe 920 also provides a constant function controlled by a [K] key on the keyboard, which is not present on the Canon machines.

The 920 was the lower-end of a pair of machines introduced at the same time, sometime in the mid-1969 timeframe. The 920 was the little-brother of the 925, which upstaged the 920 by virtue of having an extra digit of capacity (13 digits for the Monroe 925, versus 12 for the 920), as well as providing an accumulating memory register.

Inside the 920, the circuit boards have Canon logos in both etch and silk-screen on them, proving the calculator was designed and the circuit boards manufactured by Canon. Other examples of this OEM relationship between Monroe and Canon is the Monroe 950, which is a somewhat up-scale version of Canon's Canon 141.

The 920 and 925 were entry-level calculators, specifically designed as low-cost machines for basic calculating needs. This particular example of the 920 was made in the late part of 1969, and has a maintenance sticker on the back that lists 12/12/69 as the date of installation. Date codes on the IC's in the machine range from 6846 (late 1968) through 6930 (Q3 '69), which seem to correlate with the installation date.

Monroe 920 with the case opened up

The Monroe 920 utilizes small-scale integrated

circuits for its logic, along with a small count of discrete components

(mostly resistors). All but one of the 66 IC's in the machine are

Texas Instruments-made DTL (Diode-Transistor Logic) devices in the

SN39xx and SN45xx-series. A single Texas Instruments 7400-series

TTL (Transistor-Transistor Logic) Quad Two-Input NAND IC is also included

in the logic. Why only one TTL device was used amongst all of the

DTL logic is a mystery. The 920 was designed using a fairly small

complement of different chips. The devices (with the device type in

brackets, and the number of devices in parenthesis following the device

part number) used in the machine are: SN3920(6), SN3925[Quad 2-Input NAND](32),

SN3931[Triple 3-Input NAND](11), SN4553[Dual 4-Input NAND w/expander](4),

SN4554[Quad 2-Input NAND](12), and the lone SN7400 Quad 2-Input NAND TTL device.

Close-up of Monroe 920 Circuit Board

The 920 uses a magnetostrictive delay line

device, manufactured by NEC in Japan, for working storage. The delay line

appears to be very similar to the

delay line used in the earlier

Monroe 950. The

delay line has a total delay of 539.5 microseconds, with one read tap,

and two write taps, with one write tap pushing pulses in that will arrive

at the end of the line in 507.5 microseconds, and the other, adding an

additional delay of 32 microseconds. Providing

injection of pulses into the line with different amounts of delay allows

shifting operations to occur by simply gating pulses into the delay line

via the different taps.

Like most electronic calculators of its

time, the 920 uses Nixie tubes as the display technology. Each Nixie

tube contains the digits zero through nine along with a right-hand decimal

point. The Nixie tube cathodes are switched by discrete transistor

(Toshiba 2SC780) drivers in combination with an unusual transformer-based anode

drivers. The transformer design simplifies the decoding

circuitry necessary, as well as providing a voltage boost for driving each of the twelve Nixie tubes as they are

multiplexed.

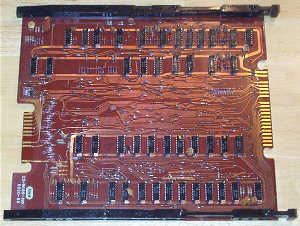

The Arithmetic (Bottom) Circuit Board

The logic of the Monroe 920 is contained on two circuit boards stacked

one atop the other across the bottom of the machine.

The top circuit board contains the Nixie tube displays, driver circuitry,

and the master clock oscillator, which uses a 2.0MHz crystal for generating

the timing for the machine, as well as the divider chains that divide the

2MHz clock down to the fundamental clock rate of 62.5KHz. A crystal-controlled

oscillator is used because it allows for accurate and stable timing of the

bits being launched into the delay line, and their recovery when the

bits reach the end of the delay line. Also included on the top circuit

board are the read and write amplifiers for the magnetostrictive delay line.

The top board contains 21 of the 66 IC's in the machine. The bottom board

contains most of the calculating and state logic, with the remaining 45 IC's

on it. The keyboard connects to the bottom board via an edge-card connector,

and the two boards are connected together by a backplane with edge-connector

sockets that are hand-wired together.

The Indication (Top) Circuit Board (with Power Supply/Delay Line Module Set Aside)

The Monroe 920 operates very typically for calculators of this vintage.

It uses adding machine style logic for add and subtract, with a key with

a white [=] legend for addition and one with a red

[=] legend for subtraction.

For multiplication and division, the problem is entered an algebraic form,

with either of the [=] keys used to calculate the result, with the

[=] key negating the result.

The calculator

uses a fixed-point decimal system, with a three position slide switch on the

keyboard panel selecting 2, 3, or 4 digits behind the decimal point. As

with just about all Canon-made calculators, the [C] (clear) key clears the

entire machine, and the [CI] (Clear Indicator) key clears only the display,

and is used for correcting input errors. The machine also features

a push-on/push-off [K] key for enabling a constant multiplier or divisor

when depressed.

It is interesting to note that the design of the machine is such

that other decimal point settings are possible by changing

feed-through jumper wires in a specific area of the Arithmetic

circuit board. A service bulletin outlines the procedure for

changing the decimal point selections, along with ordering information

for adhesive labels which are used to cover over the default

decimal point selection legend on the front panel of the calculator.

A View of the Power Supply and Delay Line Module

One weakness of the 920 and 925 calculators is that they do not support

negative numbers. A negative result is displayed as the ten's complement of the

negative number. For example, 10 - 15 results in 9999999995.00

(with the decimal point set at two digits behind the decimal point).

Pressing the [=] key after a known negative

result is generated

will immediately complement the number (with the example returning 5.00).

This weakness could prove somewhat problematic for financial users, where

the ability to clearly indicate a debit balance is important.

The 920 detects overflow

conditions reliably, and indicates an overflow or input error (such as two

keys pressed at once) by lighting a neon indicator positioned at the left end of

the display in the shape of a left-facing arrow (another Canon characteristic).

When the machine overflows, it ignores keyboard input, and requires a press

of the [C] key to continue. The 920 doesn't know that dividing by zero is

impossible, and cycles in futility trying to find an answer to an unsolvable

problem without lighting the overflow indicator. Pressing the [C] key in

such a situation will return the machine to normal. Interestingly,

pressing the [CI] key while the machine is churning away trying to divide by

zero results in the machine unlocking, but doing strange things

ranging from lighting up all of the decimal points but doing nothing,

to accepting numeric input but not performing any math operations.

Again, pressing [C] when the machine is in this strange state will restore

the machine to normal.

Detail of Magnetic Reed Switch Keyboard

The 920 uses a magnetic reed-switch keyboard that is very reliable, and

was the predominant keyboard technology of the time. The picture above

clearly shows how this technology works. The fact that there is no

physical connection between the key and the switch itself makes these

keyboards last a very long time. This is why many of these very old

calculators still have keyboards that work as they did when they were new,

whereas later calculators that used other forms of direct contact

keyboards have gotten bouncy (entering multiple digits for one key press) or

have quit working altogether.

The 920 is quite fast for a machine of its vintage.

By observation, the machine spins through math pretty quickly.

9999999999.99 divided by 1 (worst-case division) takes just over 1/3

second to give a result, and addition and subtraction

give virtually instantaneous results. Published specifications

for the machine state that addition and subtraction take a maximum

of 20 milliseconds, and with multiplication and division returning a result

in no more than 350 milliseconds. The machine does not blank the display

during calculation, so some action of the Nixies can be seen on

operations that take longer to perform. The machine also lights up all

decimal points when it is busy calculating.