| +Home | Museum | Wanted | Specs | Previous | Next |

Wang 720C Advanced Programming Calculator

Updated 5/14/2021

After searching for quite some time for one of these wonderful pinnacles of Wang Laboratories' calculator technology, someone turned me on to not one, but two! Sadly, these machines had been left to languish in an outdoor storage area for years after they were taken out of service, and they were subject to the some of the ravages of the elements. The storage area was covered, but didn't have walls, and thus, the machines, while kept out of the rain, were subject to humidity, bugs, dust/dirt, cobwebs, and mice. The machines were rescued from this situation by a scrap dealer, who very fortunately realized that these were too cool to scrap, and, as luck would have it, contacted me. Even though the machines were in pretty rough condition, with two machines, it was possible to piece together and perform restoration of this machine to complete and fully operational condition.

Later, due to the kindness of Ms. Janet Harrison and other members of her family, another Wang 720C, along with a great deal of documentation and other materials, and a Wang 711 I/O Writer were donated to the museum. This equipment was owned by her father, Thomas Harrison, who passed away in 1996. Mr. Harrison used the Wang 720C in his mechanical engineering consultancy as a high-tech leg up on competitors that had to rely on simple desktop calculators. Sincere thanks to Ms. Harrison and her family for making Mr. Harrison's prized equipment a lasting exhibit in the Old Calculator Museum.

The Wang 700-series calculators were the high-point of Wang Laboratories' electronic calculators. After releasing the 700-series, updated versions of the architecture were created; the business-oriented 600-series calculators, and the lower-cost scientific alternative to the expensive 700-series machines, the 500-series. As the 1970's progressed, the calculator business changed dramatically with the advent of LSI (Large Scale Integration) integrated circuits. LSI chip sets condensed the entire functionality of a scientific calculator down to a handful of IC packages. Handheld calculators were becoming prolific, and margins in the calculator business were dwindling due to low-cost calculators manufactured in Japan. Dr. Wang realized that his company could not make itself a force in the semiconductor business soon enough to make a difference, and that as LSI technology took over, his calculator business would be at the mercy of the chip manufacturers. He rightly decided to gradually phase Wang Labs out of the calculator business, concentrating the engineering resources of the company on developing word processing and small business computer systems. Wang Labs continued to sell the 700-series calculators and their predecessors into the late 1970's, but by that point, handheld calculator technology could replace much if not all of the functionality of such desktop behemoths, and microcomputers had begun to advance to the point where they were easier to use and program than a programmable calculator like the Wang 720C.

The Elektronika D3-28

Image Courtesy Konstantin Zeldovich

Before going into the history of the Wang 700-series calculators, it's very worthwhile to relate an interesting story about a Soviet-made clone of the Wang 700. It is said that imitation is the most sincere form of flattery. Well, the Wang 700 proves this to be true. Apparently, somewhere in the Soviet Union, the Wang 700 caught the attention of some authority involved in Soviet technology, and the machine was thought of highly enough that they decided to build a machine of their own that at least matched the Wang 700. This machine was called the Electronika D3-28. The Soviet-built calculator is, for all intents and purposes, a functional replica of the Wang 700, but packaged in a much more sleek, refined, compact, and service-friendly cabinet, with a cabinet design reminiscent of HP's competitor to the Wang 700-series, the Hewlett Packard 9810.

Profile View of the Elektronika D3-28

Image Courtesy Konstantin Zeldovich

The D3-28 was introduced in the late 1970's (seven or eight years after Wang's introduction of the 700-series calculators), and was produced well into the early 1980's. The machine pictured here appears to have been manufactured in 1981, based on a date listed on the model/serial number tag, as well as from date codes on various parts within the machine. The D3-28 utilizes very similar technology to the Wang 700, including a copy of Wang's unique wire rope ROM for microcode storage. Like the Wang 700, the D3-28 is implemented using small to medium-scale Integrated Circuit design. The IC's used in the machine are of the Soviet K155 family, which are very similar to US-made 7400-series TTL devices. In some cases, the K155 devices are even pin-for-pin compatible 7400-series devices. The only real departure in the design of the D3-28 is the use of integrated circuit RAM chips (K565RU1A memory devices) as opposed to the magnetic core memory used in the Wang 700-series calculators. By the time the Soviet version was introduced, integrated circuit memory was more cost-effective than core-memory technology, and was much easier to interface to. The microcode ROM of the D3-28 has the same 43-bit microcode word size as the Wang 700, indicating that perhaps the microcode is variant of the microcode for the 700. There are some signs that the microcode, while very similar to that of the Wang 700, is not an exact copy of the Wang microcode. An example of a subtle difference is that the D3-28 provides five digits for the program counter display when in "LEARN" mode, versus four digits on the Wang 720C. It is possible that the Soviet machine, by virtue of its larger solid-state memory, may have subtle microcode changes to allow it to address more memory than the 700-series machines.

The Wire Rope ROM of the Elektronika D3-28 (left). Compare to the ROM in the Wang 720C (right)

D3-28 ROM Image Courtesy Konstantin Zeldovich

It seems very likely that the Soviets got their hands on a Wang 700 and reverse-engineered it, and along the way, incorporated changes necessary to adapt the Wang design to their available technology. The D3-28 uses two seven-segment gas-discharge display panels (similar to Burroughs Panaplex devices) rather than the dual-row Nixie tube display of the Wang 700-series machines. The Soviet machine, like the Wang 700-series calculators, provides a cassette tape drive for storing and retrieval of programs and data. The keyboard design is quite different than that of the Wang 700 calculators, with the keyboard using more conventional key-switches rather than the micro-switch design that Wang used. Also, the various mode control switches are integrated into the keyboard (with LED indicators to show which mode the machine is in). While the keyboard design is different, the layout is very similar, with key groupings the same as Wang's machine, and in many cases, the same functions on each key location. Like the Wang 700-series, the area above the special function/addressing keys is provided for strips which can be used to provide user-defined labels for the keys.

Profile View of the Wang 720C

The story behind the Wang 700-series

calculators is a story that repeats itself time and time again in the realm of

high technology business -- the story of vaporware. Vaporware refers

to the advertisement of equipment that is not yet in production, or perhaps

isn't even yet in operational prototype form in its worst case. Technology

companies, especially back in those days, would frequently advertise products

as if they were real products, even though they hadn't yet produced any of

the product. This was seen as a way to get customers to pre-order the product,

allowing the sale to be booked even though the product might not be delivered

to the customer until significantly later. In such advertising, mock-ups

or dummy versions of the calculator being offered were used in the photography,

and the specifications stated were best guesses of what may be those

of the production machine in its final form.

On top of the high-end calculator marketplace with its

300-series calculators, Dr. Wang felt that his company could divert some of

his company's engineering resources to compete in the commercial computer

market. This market was dominated by IBM, along with Wang's neighbor

located in Maynard, Massachusetts, Digital Equipment Corp. (DEC), and a

smattering of other players such as General Electric, RCA, Burroughs, and

Control Data. Dr. Wang wanted his company to build a computer that could

compete head-to-head with IBM's wildly successful IBM System/360, and win.

Dr. Wang wanted a computer that Wang Labs could enter into the marketplace

that would be less expensive than IBM's computers, yet provide the same type

of functionality.

Wang Laboratories had a major cash cow with the extremely

successful 300-series electronic calculators (an example being the

Wang 360SE), and had plenty

of money to fund the development of a computer to compete with IBM.

the 300-series

calculators were a design that was created in the mid-1960's, and the

technology of the machines was rapidly becoming dated. Electronics

technology had changed quite dramatically during the few short years

between the design of the 300-series calculators and early

1968 when the design of Wang's computer system began. Integrated circuit

technology had started to become a reality, which made it possible to jam

more complex circuitry into a significantly smaller package. While Wang

Labs was resting on the laurels of the success of the 300-series, spending

lots of money developing a computer to compete with IBM,

other established electronics companies as well as various upstart

entrepreneurs were realizing that IC technology could be used to build

calculators that could be used to steal lucrative market share from Wang.

The rather intimidating control panel of the 720C It was March of 1968, and the design of

Wang's new computer system was moving along at a good pace. Dr. Wang and

some of his senior folks went to New York City to the IEEE Electro Conference

being held there. Little did Dr. Wang know that a machine was being demonstrated

in a private suite at this event that would put Dr. Wang and his company

in a panic. Bill Hewlett, one of the founders of Hewlett Packard, and a man

whom Dr. Wang was familiar with, invited Dr. Wang to come see

"something" in one of their private show suites. In the room was one of a

limited number of pre-production prototypes of the HP 9100A electronic

calculator. Dr. Wang, Bill Hewlett, Barney Oliver (9100 Project Leader), and

Tom Obsbore (Chief 9100 Architect Contractor) were there when Dr. Wang got his

chance to see the 9100A. After a few minutes of seeing the amazing speed,

power, and accuracy of the 9100, Dr. Wang was visibly shaken. He thanked Bill Hewlett for showing him

HP's latest brainchild, and let the room muttering

that he must "get to work". The realization that Dr. Wang felt at the moment

was that the 9100A made Wang's 300-series

calculators look like dinosaurs in comparison. Even the programmable Model

370 and 380 Wang calculators simply did not have the features, speed,

and functionality that the 9100A (and a later, the

even more capable 9100B) had going for it. The

9100 was indeed a market breaker, and Dr. Wang knew something had to be done

to counter it, and fast, or Wang's dominance in the high-end calculator

market would soon end.

Even though the HP 9100's were based on transistorized technology like

the 300-series Wang calculators, the HP machine leveraged an amazingly

innovative microcoded design (a concept previously applied to

the design of computers) to wring the ultimate computing power out

of the size limits of a transistor-based desktop package. Not long after HP

began shipping orders for the 9100A calculator in September of 1968, sales

of Wang's 300-series machines started dropping dramatically.

But, thanks to Bill Hewlett's "wake up call", moves were already afoot

within Wang Laboratories to counter HP's wunderkind.

Dr. Wang went to the folks designing Wang Labs' new computer and told them

to turn the design into a high-end programmable calculator. Dr. Wang's

reasoning was that any computer can be made to act like a calculator by

just changing the programming, which was true, and comparatively trivial

to implement (as opposed to redesigning hard-coded logic). In fact, the

computer being designed was to use a microcoded architecture similar to

that of the IBM 360 computer. Micro-coding uses a ROM (Read Only Memory)

to store very low-level instructions that guide the transfers of data and

operations

performed on data within a generalized set of registers and logic units.

Since the computer being designed was based on this microcoded

architecture, all that was needed was some additional hardware (Nixie tube

display system, specialized keyboard, and other calculator-specific

hardware changes), scaling down of the microcode to control a smaller

calculator-specific register and processing architecture, and the writing of

the new microcode to make the system operate as a calculator rather

than a computer. Dr. Wang ran a very monolithic company; essentially,

everyone reported to Dr. Wang. Even though there were other reporting

structures in place, everyone had a dotted-line reporting structure to

Wang. This meant that whenever Dr. Wang had a big project in mind, anyone's

priorities could very quickly change. It's clear that Dr. Wang's preview of

the 9100A in New York instantly changed his mind about trying to do battle

with IBM, and focus more on saving his calculator business - and indeed, Wang's visions

of conquering IBM faded quickly from the forefront of his mind (though they

never really did go away).

The principle hardware designer for the "IBM-beater" computer

project at Wang was a man named Dave Moros. Moros had come to Wang Labs as the

result of Wang's acquisition of a company called Philip Hankins, Inc., or

PHI for short. PHI was a programming and computer service bureau with

it's own IBM System 360/65. Moros was a skilled programmer, but proved

to be very adaptable, and quickly understood the hardware side of

what made computers tick. Moros, along with Koplow, were tasked with the job

of converting the logic design for

the computer into a high-end calculator. Mr. Shu-Kuang (S.K) Ho and Mr.

Don Dunning were tasked with taking the logic designed by Moros and

turning it into real hardware. With these key people in place, the hardware

side of the new calculator project had critical mass.

One critical resource needed to get this calculator project

going was missing -- the microcode to make the calculator

run. Dr. Wang pitted some of his most brilliant engineers

against each other in a high-pressure, tight-deadline contest to very

quickly generate the most efficient microcoded math algorithms

for the new computer-turned-calculator.

As opposed to most computers of the time, a high-end calculator must be able

to operate on floating-point decimal numbers, and, along with the four

basic math functions, must also be able to perform more complex math operations

such as logarithms and square root. On top of this, the calculator must

fit on a desktop. These requirements add a level of complexity to calculator

microcode that can be typically be ignored when designing a computer.

As a result, extremely efficient microcode was needed to be able to implement

all of the functions the calculator required, and still allow the code

to fit within the limited capacity of the transformer-based ROM technology

that Wang had developed as the microcode store for the computer.

Along with the microcode size constraints, the microcode algorithms themselves

had to be very efficient, allowing the new calculator to

be generate answers as fast as or faster than the competition, yet still

retain the high level of accuracy that Wang calculators were known for.

Harold Koplow, August, 1968 One of the participants in this contest

was a young engineer named Harold Koplow. Koplow had been hired on

at Wang Labs as a programmer writing applications for Wang's Model 370

programmer for the 300-series calculators. Koplow seemed to have an

intuitive understanding of how to wring the most capability out of the

limited capabilities of Wang 370...which seemed just the skill set needed

to design the microcode for the new calculator. Koplow ended up winning

the contest, designing microcode that took the fewest microcode instructions

to implement a given function.

Koplow's brilliance and perseverance in the

development of the microcode for the Wang 700-series calculators helped

to vault him into the role as Wang's senior calculator engineer after

the 700-series project was finished. After the 700-series project, Koplow

was a primary figured in the development of Wang 500, 600 and

100-series calculators. Later, Koplow was instrumental in the creation

of Wang's word-processing systems, which became Wang's big

"next generation" cash-cow business after the company left the calculator

business toward the end of calculator market shakeout of the mid-1970's.

Cover of February 24, 1969 Edition of "Product Engineering" Magazine

In December, 1968, Wang Labs announced the new 700-series calculator

to compete directly with HP's 9100 calculators. As many people who know

high-tech industry understand, the announcement of a product doesn't necessarily

mean it exists. Even back in late 1968, the notion of "vaporware" existed,

and Wang's introduction of the 700-series was just that. Even though the

product had been announced, shipments weren't promised to begin until

mid-1969, which, as it turned out, was a milestone that Wang missed by nearly half a year.

In February of 1969, McGraw-Hill Publishing's Product

Engineering magazine published a cover-story on the new (and not yet

available) Wang 700, featuring a proud, cigar-toting Dr. Wang surrounded

by a number of 300-series keyboard/display units and his new baby, a prototype

Wang 700 (which was likely a mock-up rather than an operational

unit).

Early Prototype Wang 700-Series Calculator

By April of 1969, Wang was distributing slick

marketing materials touting

the new machine, with indirect but rather obvious

comparisons between the new 700, and Hewlett Packard's 9100.

This early marketing literature was clearly developed from engineering

specifications and prototypes, and didn't accurately reflect what turned out

to be the actual product. An example of this is in a section of the literature

explaining the performance of the calculator. It is stated, "The 700 is

the fastest by far.", with performance figures quoting an addition or subtraction

in 300 microseconds, multiplication in 3 milliseconds, logarithm in

15 milliseconds, and ex in 35 milliseconds.

The actual performance the production calculator delivered were

substantially slower (though still quite fast), with addition/subtraction

in 1.7 milliseconds [almost 6 times slower than quoted], multiplication

in 12 milliseconds [4 times slower], logarithm in 47.2 milliseconds

[about 3 times slower], and ex in 61.8 milliseconds

[just under half as fast]. The changes in the speed of the machine

compared to early marketing literature are likely the result of

aggressive marketing-driven specifications which had to be backed off

when the reality of the electronic implementation became clear.

Even so, the 700-series calculators are placed among the fastest

high-end electronic desktop calculators of the era. Even today the

Wang 700-series calculators are superior in speed to some of today's

advanced calculators.

Finally, an entire fourteen months after the initial announcement,

in the February 1970 edition of Wang Laboratories' monthly publication, the Wang Laboratories

"Programmer", an official

announcement article for the Wang 700

was published, not so subtly bragging that the machine was the fastest and most capable

electronic calculator on the market. Wang Labs used over a year of

hyping the 700 to the marketplace as a means to try to assure

current and potential customers that they had a machine that could

counter the HP 9100A/B calculators, and through it would be ready

"soon", that they could place advance orders for the machine

and be first in line to get one when it became a reality.

The prototype machines shown in the early marketing materials and the press

coverage looked similar to the

final production unit, but a number of differences stand out. Most notably, the

cassette deck in the prototype was positioned differently, with horizontal

cassette loading rather than the vertical loading that came to be in the

production unit. It almost appears that a consumer-grade cassette recorder

was adapted to fit in the unit. This was replaced by a totally different

mechanism in the production units. There were also subtle differences in the

keyboard layout, with the most obvious being the absence of the pushbutton

switches controlling the mode of the calculator. Also, the prototype

did not have the large fan on the back of the cabinet...a later add-on that

was necessary due to the electronics of the machine generating more heat

than could be cooled by simple convection.

Later Prototype Calculator with

Vertical Loading Cassette Drive A later advertisement for the 700-series

shows the changeover to the vertical-loading cassette drive, but with a

bezel-color (black) door rather than the final beige cassette door

used on the production machines.

The delays that Wang experienced

in getting the 700 calculator into production were a benefit

to competitors, especially Hewlett Packard. The time between Wang's

announcement of the new machine and the time that the machine was actually

shippable was well used by Hewlett Packard and others lure more sales away

from Wang's bread-and-butter calculator business. The engineers working on

Wang's computer project were put on a drop-dead schedule to meet the promised

mid-'69 first customer ship deadline. As it turned out, the deadline

was missed...by a serious margin.

Pre-Production Wang 700A, Late 1969 By late 1969, Wang Labs have finally

got all of the details of producing what was the Wang 700A calculator sorted

out. Pre-production machines had been built and were going through

various testing processes to assure that they would survive the rigors

of shipping and day-to-day use. The machines where drop-tested and vibration

tested, checked for proper operation at marginal mains power, safety tested

for proper grounding and short-circuit protection, and subjected to extreme

heat, cold, and humidity conditions to assure that the calculators would

survive just about any conditions that they could be subjected to.

These pre-production calculators were never intended for sale to a customer, but

were used as demo machines for trade shows, field sales offices, and customer

loaners if the customer machine required a visit to the shop for repair. As

shown above, a pre-production machine was also used for some somewhat

begging advertising for the

calculator beginning in February of 1970, stating that the machine was in

production and finally, long-standing orders were finally read to be

fulfilled.

Built-in Cassette Tape Drive for Program Storage

Computer systems of the time were generally not desktop devices, usually taking

up space in an equipment rack. The design for the computer that Wang's

engineers were working on wasn't really intended to fit on a desktop.

The computer was designed to be integrated into a desk, with the area

where the file drawers would be on a regular desk packed with the electronics

that make up the computer. This design needed to be shrunk down quite

dramatically to make it into a desktop package. There simply wasn't enough

time. When a big electronics industry trade show where the 700 was to make

its debut rolled around, eager customers were expecting to see Wang's

wonderful new machine that had been marketed strongly and praised by

the press. Some devout Wang customers had already placed advance orders

for the machine. The problem: It wasn't ready! A prototype of

the electronics of the calculator existed and worked well, however,

the electronics were still too large to fit inside the package that had

been designed for the desktop calculator.

So, the engineers put the keyboard, display, and cassette deck into one of the

cabinet mock-ups for the 700-series machine, bolted that cabinet to a

table-top, and fed a big bundle of cables out of the bottom of the cabinet,

through a hole in the table top, to a hidden area under the table that

contained all of the electronics of the calculator.

What the attendees of the trade shows saw was a very powerful and

advanced calculator that, while rather large, still fit on a desktop.

What they didn't know was that the rather chunky looking

cabinet they saw contained mostly air. The deception was a success, at

least for a while. Orders for the 700-series machines started pouring in.

While orders are great, sales are what keeps a company going, and still,

Wang had nothing to sell. Wang's salespeople were advised to placate

irritated customers whose orders for 700-series calculators were not being

filled by providing them with loaner high-end 300-series calculator systems

until their orders for the 700-series machines could be fulfilled. Finally,

slightly behind schedule in the 3rd quarter of 1969, the first production

Wang Model 700 calculators were rolling off the assembly line.

Photo at a Trade Show in September, 1970, with Wang 700-Series Calculator(left) and Model 701 Output Writer(right). One of the biggest problems Wang had

with the early 700-series calculators was cooling. The electronics were really

designed to be in a computer cabinet rather than a comparatively small

desktop calculator. As such, the early 700-Series calculators had some

pretty serious problems with overheating.

Early Wang 700A with Convection Cooling (No Fan) Originally, the machines were

designed for convection cooling, with vents in the base of the chassis and

top of the cabinet. This didn't work well at all. In fact, Wang salespeople

had to adopt an interesting, if bit misleading strategy to prevent potential

customers from realizing that Wang had a problem with the cooling of the

calculators. Salespeople demonstrating the machine at trade shows or

customer sites learned

quickly that the early 700-series demo calculators would start to exhibit

strange symptoms after operating for around 15 minutes because they would

overheat. So, they would demonstrate the amazing capabilities

of the calculator for about ten minutes, then they would turn the machine off

and pull off the top cabinet (fortunately, it was very easy to remove), showing

off the high-tech innards of the machine, conveniently allowing the machine

to cool off while they were explaining the wonders of Wang's use of integrated

circuit technology.

Later 700-Series Machines Used Forced Air Cooling

After a few minutes of showing off the insides of the machine, the machine

cooled enough for the electronics to be happy again, the cover went back

on, and the salesperson started the spiel all over again. It soon became

clear that real customers wouldn't relish having to operate their

machines without the cover, so a production change was implemented,

involving the addition of a good-sized fan mounted on the back of the cabinet.

The fan provided forced-air cooling for the electronics, eliminating the

cooling problems, but somewhat corrupting the lines of the machine,

not to mention adding fan noise to what before was a silent instrument.

Dr. Wang's redirection of his

computer effort was a success, at least for a little while. The 700-series

calculators did quite well in the marketplace, proving to be worthy

competition for HP's 9100's. However, during the time that Wang was working

on hammering out the 700-series, HP was busy designing a new line of

calculators that would truly blur the line of definition between a computer

and calculator...the 9800-series, a triple-whammy assault of powerful

calculators that would spell the beginning of the end for Wang in the

calculator business.

The HP 9810A, introduced just a little more than

a year after the Wang 700-series calculators began shipping, used large scale

IC technology, and was more than a match for the 700-series machines.

To complete the three strikes against Wang, shortly after the 9810A was

introduced, HP announced the 9820A Algebraic

calculator and 9830A, a computer-like calculator

programmed in BASIC.

Under the cover of the Wang 720C. The Wang 700-series machines underwent a

number of revisions as the product line matured. The 720C featured here

is the highest-end machine in the 700-series.

There are two main flavors of the 700-series calculators, the 700, and the

720. The Model 720 machines received double (16K bits) the amount of

core memory capacity of Model 700 calculators. The original machine in

the series was the 700A, with the 720A providing twice the memory capacity.

The -A version machines were quickly superseded by the -B version machines.

The -B version of the 700/720 involved some design improvements, with the major

change being the addition of new microcode to the ROM to allow interfacing of

the Model 701 Output Writer or

702 Plotting Output Writer

devices. The -C versions were a later

update, including some minor circuit board updates, but mainly incorporating

additional microcode modifications to add some new operations to

the calculator's instruction set. The -C microcode changes added

math (mostly decimal point positioning) instructions, along with

instructions to handle transfers to/from main memory from an external

memory expansion interface (Model 708-1 External Memory

Controller, and Model 708-2 External Memory Modules).

Wang Labs designed the 700-series machines to be retrofitable, meaning that

it was possible to upgrade a 700B to a 720C in the field by simply

changing circuit boards, core memory, and ROM. The 720C exhibited here appears

to have been a benefactor of such an upgrade, with a new model/serial number

tag affixed over the top of the original Model 720B model/serial tag.

The Dual-Register Nixie Tube Display of the 720C One of the most striking features

of the 700-series calculators is the display. All of the machines

in the series have a dual-register Nixie tube display...more Nixie tubes

than any other Nixie calculator that I'm aware of. The display is arranged

in two rows of 16 tubes each. 12 digits are used for normal numeric

display, or for the mantissa on numbers displayed in scientific notation.

A special sign Nixie (which actually contains a +, -, 8, and left and

right-hand decimal points) is located at the left end of each row for

indicating the sign of the number in the display (the 8 and left-hand

decimal point in this tube are not used). Separated slightly and to

the right of the mantissa display is the exponent display, consisting

of another 'sign' tube, and two numeric tubes. The numeric Nixies

contain the digits zero through nine, and both left-hand and right-hand

decimal points, but only the right-hand decimal points are used. The tubes

themselves are labeled as Wang parts, with Wang part numbers, but it's

most likely that they were manufactured to Wang specifications by

Burroughs.

One of the Nixie Driver Circuit Boards

The Nixie tubes plug into sockets mounted on circuit

boards that connect to the Nixie driver circuit boards by a cable terminated

with edge-connector fingers. The two arrays of Nixie tubes are mounted

in an aluminum extrusion that provides a framework for holding everything

in place. A foam-rubber strip across the tops of the tubes provide shock

isolation and positioning for the tubes. Two identical driver circuit

boards contain the circuitry to drive the Nixie tubes, including a TTL

decoder chip, and discrete transistor driver circuitry. The Nixie display

is multiplexed, meaning that each Nixie displays its digit in a timeshared

fashion, with the timesharing occurring at a fast enough rate that the

human eye perceives all of the Nixies illuminated at once.

The Nixie Tube Display Module The bottom display register is called

the "X" register. This register is where all numeric entry occurs, and results of scientific functions (for example, square root)

are placed here also. The top register is the "Y" register. This register

can be used in a number of ways, but has three major uses. First, it

can get a copy of the number currently in the "X" register by the user

pressing the [^] (up arrow) key. The Y register also acts as an

accumulator, automatically accumulating the results of addition or

subtraction functions. Lastly, the Y register displays

the results of multiplication or division operations. The displays

have fully floating decimal, and automatically switch to scientific notation

when the number is too large to be displayed conventionally. Numbers

are displayed left justified in the display, and trailing zeros

are not inhibited. Numbers displayed in scientific notation are displayed

in a somewhat unusual format, being left-justified, with the decimal point

always before the first digit. For example what would normally be written

as 5.0x10-15 would display as "+.500000000000 -14". You can see

examples of the display in scientific notation in the photo above.

The backside of the Keyboard Key Assembly Another distinguishing feature of the

Wang 700-series machines is the vast keyboard on the machine. There are

a total of 83 keys on the machine, and at first glimpse the sheer volume

of keys can be intimidating. The keys are grouped by function, with further

visual cues of color-coded key caps to help the user quickly find the function

they are looking for. Clear key caps are generally related to numeric entry

and control functions, blue key caps indicate higher-level math functions

and other specialized functions, rose-colored key caps are related to data

storage and retrieval, and smoke-gray key caps designate programming and

program control functions. The keys themselves are an unusual

design. The design of the keys harkens back to the original Wang

LOCI-2 electronic calculator, Wang's first entry into the marketplace.

The only real difference in the design of the keyboard between the

LOCI-2 and the 700-series machine is that the key caps on the 700-series

machine are smaller, due to the sheer volume of keys on the 700.

The keys consist of a flat plastic square sitting on the top end of a stalk.

Over the top of the square, a paper legend containing the nomenclature for

the key is placed, then covered with a snap-on plastic cover that

retains the nomenclature on the key cap. The snap-on cover is made of

clear (or tinted) plastic to allow the key cap nomenclature to show through.

The Keyboard Circuit Board, with myriad Micro-switches The stalk of the key is square, and fits

through a square hole in the keyboard panel. On the back-side of the keyboard

panel, a round plastic disc (looks like a plastic washer) is pressed onto the

stalk, such that the disc is perpendicular to the stalk. This disc rides on

the plunger of a circuit board-mounted micro switch, such that when the switch

is pressed, the plunger of the micro switch is depressed, activating the switch.

The spring pressure of the micro switch pushes the key cap back up when the

key is released. This makes for a keyboard that has very little key

travel, but works surprisingly well, is mechanically very simple, and

is extremely reliable. The keys on the 720C in the museum work as well

today as they did when the machine was brand new, with no bounce or

false entries.

The Bare Wang 720 Chassis Moving inside the machine, it's clear

that Wang designed the machine to be modular. Most of the guts of the

machine, except for the microcode ROM array, are situated on a sturdy

thick-gauge aluminum chassis. The chassis contains the edge-connectors

that the circuit boards plug into, the power supply (which is also modular),

and mounting points

for the Nixie tube display subsystem and the cassette tape drive.

The back panel of the chassis is exposed through a cutout in the back

portion of the lower half of the case of the machine, and has connectors

for I/O expansion and a printer, along with a fuse holder, power switch, and

strain-relief for the power cord.

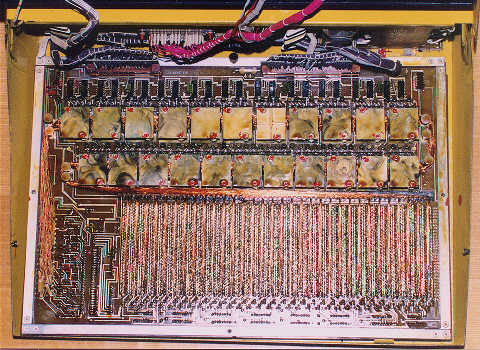

The Hand-wired Backplane of the Wang 720C It seemed that Wang Labs wasn't

afraid of building machines that were labor intensive to make. Many of

Wang's machines used hand-wired backplanes to interconnect the circuit board,

and the 720C was no exception. The backplane is a maze of multicolored wire

strung point-to-point between the long pins of the edge connectors.

Most of the backplane wires connect to the edge connectors with clips. The edge

connectors have long square-pin tails which the clips connect to.

The clip forms both a mechanical and electrical connection between the

wire and the edge connector. The edge connectors are framed by a large

circuit board with cutouts in it so the edge connector pins can stick

through. This circuit board serves as a power distribution plane for routing

the power supply voltages needed for most of the logic in the machine.

The Circuit Boards of the 720C The majority of the logic of the 720C

lives on group of twelve plug-in circuit boards containing a combination of

small-scale DTL (Diode-Transistor Logic) and TTL (Transistor-Transistor Logic)

integrated circuits. A total of 315 IC's make up the logic of the

machine, along with a large number of transistors, diodes, and other

discrete components. The TTL parts are all standard 7400-series devices,

however, many devices have Wang-proprietary part numbers on them of the

form 376-xxxx. It appears that Wang used these internal part numbers on

standard devices in order to keep the service and parts

sales for these machines to their own service organization. Along with

that, Wang probably wanted to make it more difficult for competitors to

reverse-engineer the machine. It appears in one case that one of Wang's

IC vendors (Texas Instruments) made a mistake on labeling some of the parts,

including both the Wang internal part number, along with the standard

7400-series part number. Wang had to paint over the 7400-series part number

to 'keep their secret'. In any case, the secret wasn't kept all that

well, because when comparing identical boards between the two machines,

there are cases where there are Wang-numbered parts that correspond to

standard parts in the same locations on comparable circuit boards. My guess

is that Wang couldn't get enough volume of the custom-numbered parts, and

had to resort to using 'off the shelf' parts in order to meet manufacturing demand.

Closer view of one of the Wang 720C Circuit Boards (Note rectangular painted-over areas on some of the parts) One problem with IC technology of

the late 1960's is that it was great at integrating logic, such as

gates and flip-flops, but the technology for providing memory, such as

RAM (Random Access Memory) and ROM (Read-Only Memory) simply didn't exist.

The computer that Wang originally set out to design was to be a microcoded

architecture. Microcoded architectures use generalized logic elements that

are controlled by sequencing electronics that read 'microinstructions' out

of ROM and direct the operation of the logic. A microcoded architecture

allows much more generalized logic to perform a myriad of tasks. The microcode

for a processor architecture is essentially a set of 'instructions' that

direct the operations of the logic of the machine.

The Ferrite Transformer Microcode Store of the Wang 720C (Component Side w/Signal Steering Diode Array) Microcoded architectures

are significantly more flexible than hard-wired logic, in that changes

to the behavior of the logic can be made by simply changing the microcode.

For example, later electronic calculators, such as those made by

Compucorp, used the same basic logic

architecture, with microcode changes giving each different model a different

set of functionality. The problem with microcoded designs was that the

microcode needed to be stored in a read-only form somewhere. At the time,

integrated circuit ROMs simply didn't exist. So, Wang had to build their

own ROM. Earlier Wang calculators used diode-based ROMs for built in

'programs' to perform trigonometric functions. However, a diode-ROM that

could hold the amount of data required for the microcode for such a complex

machine would be prohibitive. So, Dr. Wang ended up using technology that he

had a hand in the development of -- a ferrite rod-based ROM.

The "Wire" side of the Wang 720C Microcode ROM The microcode ROM is a good example of

Wang Labs' fearless attitude with regard to labor-intensive designs. While the

component side of the ROM board is interesting, with literally thousands of

tiny diodes (used for routing signals through the wiring of the ROM) soldered

into place. While tedious, automated equipment could be used to place and

solder these diodes. The other side of the circuit board is

where the labor intensive part comes into play. Literally thousands of

hair-like strands of enameled magnet wire are strung across the board, stretching

from the diode selection logic up through wire guides, and into

square-shaped plastic fixtures at the top of the board. In early

700-series calculator prototypes, each of these

tiny wires had to be hand-threaded, a task that used over 5000 feet of

enameled wire, and took six and a half weeks to complete. Obviously, manually

wiring the ROM was out of the question. Dr. G. Y. Chu, one of Dr. Wang's

closest friends, co-founder of Wang Laboratories, and, at the time, Wang

Labs' senior staff engineer, devised a semi-automatic

"weaving machine" that assisted a patient operator in the process of wiring

the ROM. While this machine significantly reduced the time required to

manufacture a ROM, it still took too long.

The Production Wang 700 ROM "Weaving" Machine In the end, the weaving machine

was augmented with additional electronics, and, interestingly enough, had

its operation controlled by a ROM very similar the one the weaving machine

was to manufacture. This augmentation allowed a ROM to be manufactured in

an automated fashion in a period of just under one day.

Dr. Chu ended up getting a US patent (3,639,965) on this amazing machine

that was granted in February of 1972. A bunch of these automated weaving

machines were quickly constructed, allowing volume production of the ROMs

for the 700-series calculators to begin. The difficulties of creating

the ROM for the 700-series machines were the primary reason behind the

delays in the delivery of Wang 700 calculators to customers.

A close-up of the Hand-Wired connections on the 720C Microcode ROM The active part of the ROM consists of

eleven square plastic structures, each of which contains four U-shaped

ferrite structures. Each of these ferrite structures

effectively serve as small transformers, with primary and secondary windings.

A winding of wire is wrapped around one leg of the U shape, connecting

to a transistorized sense amplifier. This winding is the secondary winding

of the transformer. The other leg of the "U" has the primary windings.

A close-up of the Ferrite transformer elements and windings If one of the wires wrapped around the

primary side of the "U" carries a pulse of current, that pulse will be picked

up in the secondary winding, be amplified by a sense amplifier, and sent

off to the microcode logic. A total of 43 of these ferrite structures are

used to make up the 43-bit microcode control word that drives the operation

of the Wang

720C. An array of TTL decoder integrated circuits, along with the gigantic

array of diodes serve to decode and select the microcode address into

one-of-2048 individual word lines. When a given word line is decoded,

a pulse of current flows into one of the 2048 tiny wires. The selected word

line wire threads its way from the selection logic, through some

plastic wire guides, then up through the array of ferrite rods, wrapping

around a rod when a '1' is to be encoded for that bit, and bypassing the

rod when a '0' is to be encoded. A similar type of technology, using

toroidal-shaped ferrite elements, was used for microcode ROM in the

Hewlett Packard 9100 series calculators, the

machines that pushed Wang to build the 700-series calculators.

The microcode ROM is organized as 2048

words of 43 bits each, for a total of 88,064 bits. Given that the circuit

board is approximately 16" x 12", that comes to a bit density of just over

458 bits per square inch. Today, we can cram 128 million bits of ROM onto

a chip of silicon a little smaller than the fingernail on your pinky finger.

720C ROM Board in place in the base of the cabinet The wire side of the ROM board is covered

by a molded plastic sheet that is taped in place to protect the delicate

wiring from damage. It is fortunate that Wang decided to provide this shield

from the elements, as it is sure that the wiring would have been damaged by

the critters that inhabited these machines while they were in storage. The

ROM microcode board occupies a good portion of the base of the machine, mounted

in the base with rubber isolating pads to prevent shocks from handling from

jarring the wiring. The ROM board connects into the main chassis of the

calculator by two edge-connectors.

Wang 720C Core Memory Board Along with having to deal with the

limitations of technology in the microcode ROM, Wang also needed to build

machine with a significant amount of random-access memory to store

user-written programs and memory registers for data storage. At the time,

integrated circuit memory chips were just beginning to be experimented with

in the laboratories of IC manufacturers. So, Wang relied on the tried and

true memory technology that Dr. Wang helped to invent...core memory.

All of Wang's earlier calculators utilized core memory to store memory

and working registers, and the 700-series machine was no exception.

The 700-series machines were Wang's last to use core memory. The later

follow-on 500 and 600-series Wang calculators used the same architecture

as the 700-series machines, but replaced the core memory with MOS

(Metal-Oxide Semiconductor) memory chips. The core memory plane in the

720C consists of 16384 cores, arranged in 8 planes. The cores are strung

on tiny gold wires. Core memory uses magnetic fields to store a single

bit in each core. The nice property of magnetic core as opposed to

semiconductor memory is that core memory retains its state even when power

is removed, meaning that program steps and data stored into the 720C's memory

years ago was immediately retrievable once the machine was brought back

to life. The core memory board itself contains only the core arrays and

diode switching circuitry. A clear plastic shield is secured to the board

to provide protection for the delicate core planes. Another board provides the various driver,

timing, and interface circuitry to allow the memory to interface with the

rest of the calculator logic.

Display with 720C in "Learn" Mode The 720C is a very capable calculator.

In addition to the usual four math functions, the machine provides

single-key solutions to square root, x2,

10x, ex, base 10 and e

Logarithms, reciprocal, absolute value, and integer functions. A [Pi] key

immediately recalls the constant Pi into the X register. The machine

also provides extremely powerful memory register functions, allowing both

direct and indirect access to memory registers. Individual function keys

provide access to directly or indirectly addressed register math

(add, subtract, multiply, and divide) between the X register and a given

memory register. Memory registers can also be stored into and recalled

directly and indirectly (with the memory register defined by the number

in the Y register during indirect operations), as well as swapped between

the X register and memory register. An unusual feature

of the 700-series machines is the [RECALL RESIDUE] key, which enables easy

multiple precision calculations to take place. In cases where results of

addition, subtraction or multiplication exceed the 12 significant digit

display capacity of the machine, this key recalls the extra digits of the

answer into the X register for use in further calculations. In division

problems, the remainder after the division is performed is recalled into

the X register by the [RECALL RESIDUE] key.

The 700-series machines are also very

powerful programmable instruments. Programming is performed using

"learn mode", where keystrokes are translated into codes that are stored

into program memory one at a time. Each keystroke consumes one 'step' of

program memory, and is represented in the machine as two two-digit

decimal numbers between 00 and 15. For example, the [2] key is represented

with the code "07 02". For a listing of the various operation codes

on the 700-series calculators CLICK HERE.

When the calculator is in learn mode, the Y register display is blanked,

and the X register display shows the current program memory location

followed by the program code at that location. Programs

can do extensive test and branch instructions, allowing looping and decision

making operations to be performed based on the results of calculations or

user input. Branching operations are performed by marking a branch

destination with a label (by pressing the [MARK] key, followed by any

other key to serve as the label), with branches to that location caused

by invoking the [SEARCH] key followed by the label to be branched to.

Conditional test operations perform the specified test

(such as Y An Early Wang Cassette Tape for Wang 700-Series Calculators A Later Wang Cassette Tape The 700-series calculators have a

built-in cassette tape drive that allows programs to be easily stored and

recalled from cassette tapes. The drive is semi-automatic, requiring that

the user properly position the tape with manual "FORWARD" and "REWIND" controls,

and making the tape ready for access by pressing the "TAPE READY" control.

The "RELEASE" control ejects the tape.

Wang 700-Series Program Library Binder The value of any programmable calculator

comes in its ability to be adapted to a wide variety of tasks, depending

on its programming. Wang realized early in their days in the calculator

business that it was a worthwhile effort to provide a library of programs

that their customers could leverage so that they didn't have to end up writing

programs themselves. Wang Labs provided an extensive library of programs

which were made available to any purchaser of a 700-Series calculator.

The library (as it existed in 1970, when the example of the library in the

museum was copyrighted) consisted of programs in eight different categories,

including Mathematics, Civil Engineering, Statistics, Mechanical Engineering,

General Science, Business and Finance, Electrical Engineering, and Utility. Each

program in the library was documented with a program description, abstract,

operating procedure, examples, a complete program listing, and in some

cases, supporting documentation such as flow charts.

Given the powerful programming capabilities

of the machines, it is only natural that the 700-series calculators

also be able to interface with a wide variety of external equipment. Wang

designed the 700-series calculators with a generalized input/output system

that allowed a wide range of peripheral devices to be connected to the

calculator. These peripherals included printers and teletype units,

external magnetic tape drives, paper tape readers, and digital I/O ports

that allowed the 700-series calculator to interface with just about

any kind of digital device. Wang published a detailed document

outlining the I/O interface of the machine, allowing customers to design

their own I/O interfaces, making the 700-series calculators extremely

versatile data acquisition and control devices. An example of this

flexibility is that NASA used a 700-series calculator during the Apollo

spaceflights as a range safety system to track lightning strikes and warn

flight controllers of unsafe atmospheric electrical conditions during

pre-launch activities. The 700-series calculators are rather fast.

All operations return results that appear instantaneous to a human

operator. A printed specification

sheet for the 700C lists approximate timing for various calculations, with

addition/subtraction completing in 300 to 500 microseconds, multiplication

and division in 2 to 5 milliseconds, and square

root (the slowest operation) completing in 25 milliseconds.

While calculations are occurring, the displays flicker ever so

slightly. The circuit board that appears to control the timing of the machine

has an 8.0 MHz crystal on it, implying that the master clock frequency of the

machine is 8 Megahertz. This master clock is likely divided down to some even

fraction of 8 MHz, probably something in the range of 500 KHz to 2 MHz, given

the type of logic used in the machine. Whatever the basic operational speed of

the machine, it is fast enough that even complex programs execute at a

fair clip. A simple program loop that continuously increments the number in the

Y register by 1 accumulates approximately 650 counts per second.

The speed of the calculator is likely an artifact of the

machine originally being designed as a computer, with logic operating

at higher speeds than most calculators. The machine has two indicator

lights on the keyboard panel for warning of error conditions; the "MACHINE

ERROR" and "PROGRAM ERROR" lamps. The MACHINE ERROR

indicator lights to indicate a fault with the machine, or

when the cassette tape device gets an I/O error. Pressing the [PRIME]

key will clear the MACHINE ERROR indicator (hopefully, assuming

there is not some kind of hardware problem) and return the

machine to normal operation. The PROGRAM ERROR lamp indicates an error

in the running program, such as a branch with destination that can't be found,

or running off the end of program memory. Pressing the [PRIME] key will

clear the machine, and the PROGRAM ERROR condition. Date Stamp on 720C Circuit Board This particular 720C appears to have

been manufactured sometime in the mid-1972 time frame. The final

Q/A inspection sticker lists a date of August 16, 1972.

Along with the date stamps provided on the circuit boards and other

components, the date codes on the IC's seem to match up

well with the build time frame of this machine.

Image Courtesy Bill Needler

Image Courtesy Bill Needler

Note Location of Wang Logo(Above Cassette Door), and missing "Wang 700 Advanced Programming Calculator" on the Cassette Door

Note no fan on the back of the 700-Series Cabinet

Image Courtesy Bill Needler

Photo from February, 1970 Wang Laboratories "Programmer" Periodical

Image Courtesy Bill Needler

Item Courtesy of the Thomas J. Harrison Family

Item Courtesy of the Thomas J. Harrison Family